Author: Dr Steve Nuttall | Posted On: 15 Aug 2025

Nearly 6 in 10 Australians want weight loss, yet only 1 in 9 use calorie tracking apps. The science says calorie balance drives weight change, but biology doesn’t always play fair. This gap between intention and action reveals something crucial about how weight management really works.

The say–do gap

Our consumer health surveys reveal a striking disconnect. While 58% want to lose weight (19% a significant amount, 39% a few kilos), actual engagement with weight management tools remains low. Only 11% used a calorie tracking app in the past year, 12% bought a fitness wearable, 5% joined a structured programme, and 6% tried prescription medications.

This isn’t about awareness or belief in technology’s effectiveness. In fact, 47% of respondents agree that apps and wearables are effective for health management. The gap suggests current solutions aren’t matching user needs or the biological reality of weight regulation.

The thermodynamic truth

Calories In, Calories Out (CICO) refers to the principle that weight change depends on the balance between energy consumed through food and energy expended through metabolism and activity.

CICO is correct in principle. Energy balance determines weight change. Apps aim to track intake and expenditure to maintain a deficit for weight loss. In tightly controlled settings, sustained deficits lead to predictable weight change every time.

This is why calorie counting can work, and why it forms the logical foundation for most digital tools. Laws of thermodynamics do not bend. But the variables in that equation? They shift dramatically in ways that make sustained deficits far harder to measure and maintain.

Why CICO often falls short in the real world

Several biological mechanisms explain why real-world weight loss differs from theoretical predictions:

- Metabolic Adaptation: After weight loss, resting metabolic rate drops 7-9% below what body composition alone would predict. That’s 50-180 calories per day. This adaptation can persist for years, as documented in “The Biggest Loser” study where contestants’ metabolism remained suppressed six years later despite weight regain.

- Hormonal Disruption: Dieting increases ghrelin (the hunger hormone) and decreases leptin and GLP-1 (satiety signals), sometimes for months after weight loss. Our bodies biochemically fight to restore lost weight, making appetite regulation increasingly difficult over time.

- NEAT Decline: Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (the calories burned through unconscious movement like fidgeting) drops by roughly 150 calories daily when dieting. People instinctively move less, often without realising it.

- Variable Calorie Absorption: Some foods (e.g. whole nuts and seeds) may yield 20-30% fewer usable calories than food labels suggest, while refined carbohydrates are absorbed almost entirely. Two diets with identical “label calories” can have different energy absorption rates.

- Food Quality Effects: Fructose intake can promote weight gain by altering hunger and metabolism independent of total calorie count. Recent research shows fructose triggers greater weight gain than glucose, calorie for calorie, through effects on brain reward pathways and liver metabolism.

CICO still applies, but the variables shift, making sustained deficits harder to achieve and maintain than simple arithmetic suggests.

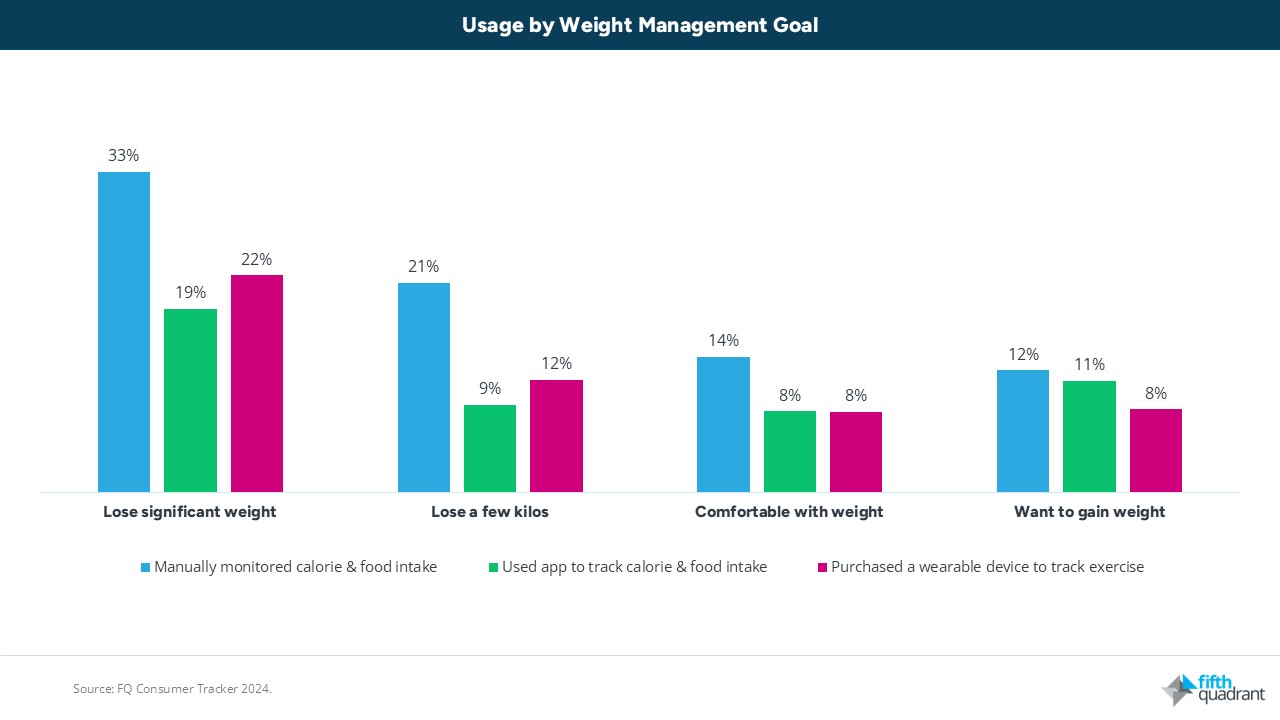

What Australians are actually doing

Our surveys reveal the practical reality behind these biological challenges.

Those who most need effective weight management tools face the greatest biological challenges. Nearly half (46%) of Australians who rate their health as ‘poor’ want significant weight loss, along with 27% of those rating their health as ‘fair’. Yet these individuals are likely dealing with metabolic complications, medications, and health conditions that make simple calorie counting even less effective.

Interestingly, around 1 in 4 (26%) of those who want to lose a significant amount of weight took no management action in the past year despite wanting change. This may not be laziness and maybe reflects the difficulty of sustaining approaches that don’t account for biological adaptation and individual variation.

Market implications: Closing the gap

For health and wellness brands, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity. Calorie counting tools may work for some, but others want solutions that blend thermodynamics with biological nuance, which may include:

- Personalised Recommendations: Moving beyond static calorie targets to algorithms that adjust for metabolic changes, individual absorption rates, and food quality factors.

- Integrated Behaviour Support: Combining appetite cue monitoring, stress management, and sleep optimisation with traditional tracking to address the psychological and physiological drivers of eating behaviour.

- Adaptive Technology: Systems that recognise when traditional CICO approaches are failing and suggest alternative strategies like meal timing, food quality focus, or exercise integration.

- Evidence-Based Education: Helping users understand why weight loss often plateaus and preparing them for biological adaptation rather than treating stalls as personal failures.

Success lies not in abandoning calorie awareness, but in building tools sophisticated enough to work with human physiology rather than against it.

Contact us for insights on designing evidence-based, consumer-centric products that close the say-do gap, partner with Fifth Quadrant to understand what really drives lasting behaviour change.

Posted in Healthcare, Consumer & Retail, TL